how innovation happens

You’ve probably all heard platitudes like “move fast and break things”, “done is better than perfect”, “execution is everything”, or “ideas are cheap”.

They might even work in some cases. But when we apply them to everything, we encourage short-term hacks rather than long-term solutions. It’s not the right approach for big, complex problems, because it drives us away from figuring out what is actually needed.

Most importantly, these hacks tend to define our new normal, so it becomes harder to think about the real issue. Of course, this is much easier to do, and so we’re tempted to settle for an increment and be happy that it is a little bit better.

But if we celebrate incremental improvement as if it is real innovation, we’re just deluding ourselves because it won’t change anything for us.

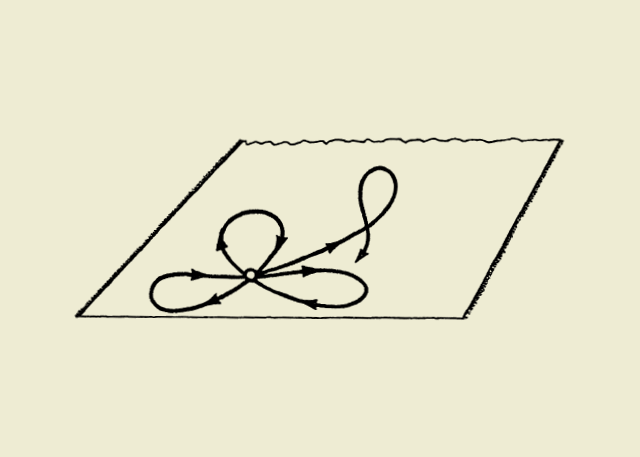

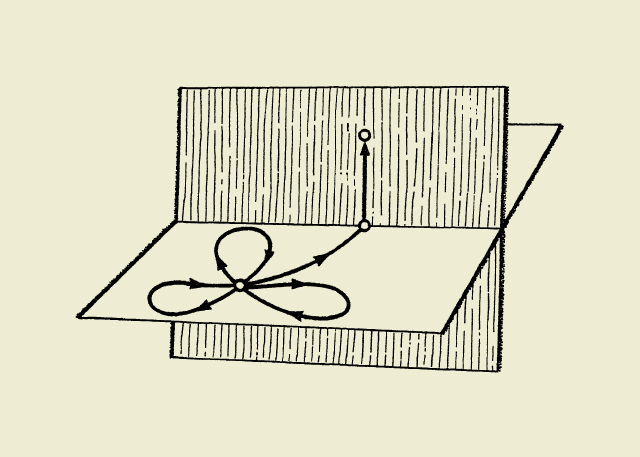

This line of thinking comes from a great novelist who researched creativity and innovation. Arthur Koestler said our minds are constrained to think within a given context or system of belief. Think of a flat, two-dimensional surface — a plane — on which you can move around freely. We can do many things on this plane: have goals, make plans, encounter problems and obstacles, solve them, or walk around them. But whatever we do, we are bound to the context of that plane. Sure, we might optimize how we solve problems, or be able to move around faster, but it is almost impossible to come up with something original or new because we are so tightly bound to this fixed context.

Innovating in this contextual plane means that we’re just getting more of the same — only an optimization of our current experience. We accept this plane as unchangeable reality, and our thought patterns are stuck in these dimensions, because this is how we grew up, and this is all we can imagine.

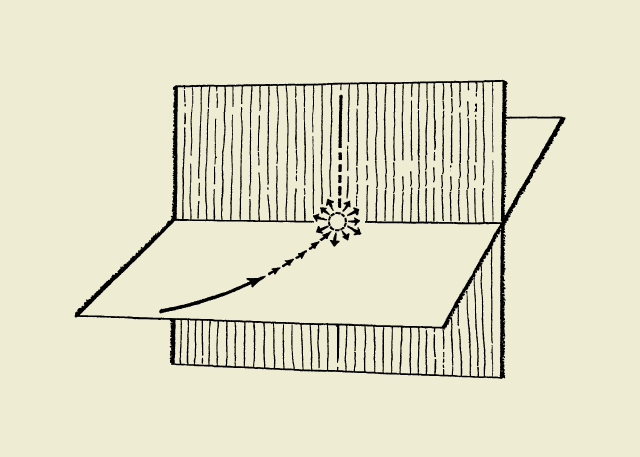

But every once in a while, when we’re taking a shower, or out jogging, we have a little outlaw thought that doesn’t really fit into this plane. We suppress it, and push it back, thinking of it as a joke, or something impractical.

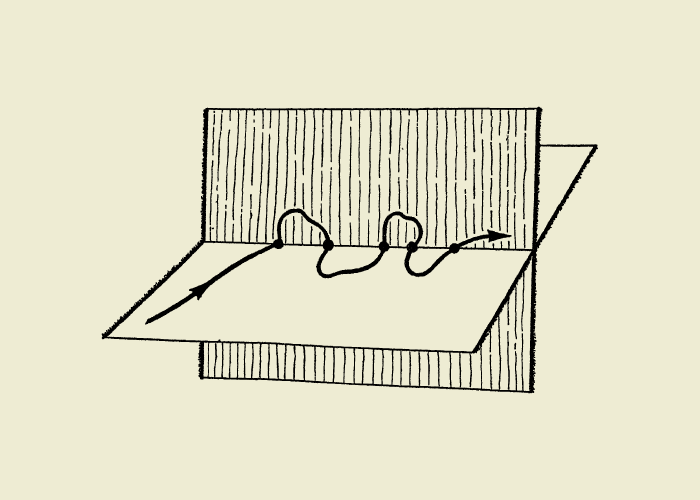

And sometimes we let these little outlaw thoughts flourish: we find out this little idea is much more interesting when expanded into a different context. A different plane! Think of it as a wall: a plane perpendicular to the one we are moving in.

When we follow our thoughts, ideas, and visions, we are trying to climb the wall, to crawl up this new plane, and explore a new context.

A few things can happen as a result.

First, our idea makes perfect sense in the new context, but it doesn’t make sense in the original one. In the original plane it seems like utter nonsense, and so we turn ourself into a crackpot for a little while. That’s one force pulling us back — not wanting to be seen as crazy. Think of Galileo trying to explain that the earth revolves around the Sun.

Second, when we’re trying to explain this idea to someone else, they need to go through a similar process. This is probably the most difficult thing about real innovation: other people have to learn to see this new context, even though it might seem incomplete, or absolutely nutty. “There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home” is just one quote that portrays this difficulty.

And third, this new context is just another plane where we can make plans, explore, and optimize. Eventually, when enough people follow the new idea, the new plane replaces the previous one, and everything starts over again. Everybody does want a computer in their home, after all — more than one.

This is how we innovate. And it matches Doug Engelbart’s ABC model nicely.

If we stay on our current plane, we are never exposed to new ideas and contexts. Yes, we might find faster ways to do things, or have clever ideas about how to solve existing problems more quickly, but without fundamental change, we’re only improving and not really innovating. We’re just getting more of the same.

Despite thousand-fold improvements along every technological dimension, the concepts behind today’s interfaces are almost identical to those in the initial Mac from the early ’80s. Almost all of today’s representations are designed for the medium of paper, limiting us to pencil-and-paper thinking. Even in the middle of a global pandemic, reeling from the economic fallout, and facing the burning need to come together as a species in the face of all these crises, we have not grasped how to share and collaborate effectively.

But at least everything looks prettier than it did 50 years ago.

If the threshold of true innovation is not reached, any improvement remains so small it’s no better than an illusion.

I am not talking about optimization, alleged innovation, disruption, the next big thing, or making things faster. We are putting ourselves in a mental state where optimization is pretty much all we can do.

In the face of the complex crises yet to come, that won’t be enough.

Want more ideas like this in your inbox?

My letters are about long-lasting, sustainable change that fundamentally amplifies our human capabilities and raises our collective intelligence through generations. Would love to have you on board.