getting better at getting better

What was your favorite toy when you were a kid?

Mine was a blue tricycle. I still have vivid memories of that three-wheeled taste of freedom. I loved it so much. I rode it everywhere until my sixth birthday, when I got an impressive upgrade: a big red bike.

Scratched knees, bruises, and tears defined the next few days as I learned to ride. They were challenging days, but I mastered it in the end.

Have any of you ever experienced something like that? Why do we do it? Why do we feel compelled to rise to the challenge despite the pain and frustration? The answer is obvious: we don’t want to be left out. My friends were riding their big-boy bicycles, and if they could do it, so could I!

But there is more to it. A bicycle is a better tool than a tricycle. A bicycle lets us travel faster, more easily, and with much less effort than a tricycle. My big, red bike gave me greater access to the world around me.

It’s a challenge to move away from familiar methods to new practices and unfamiliar ways of thinking: everything has a learning curve.

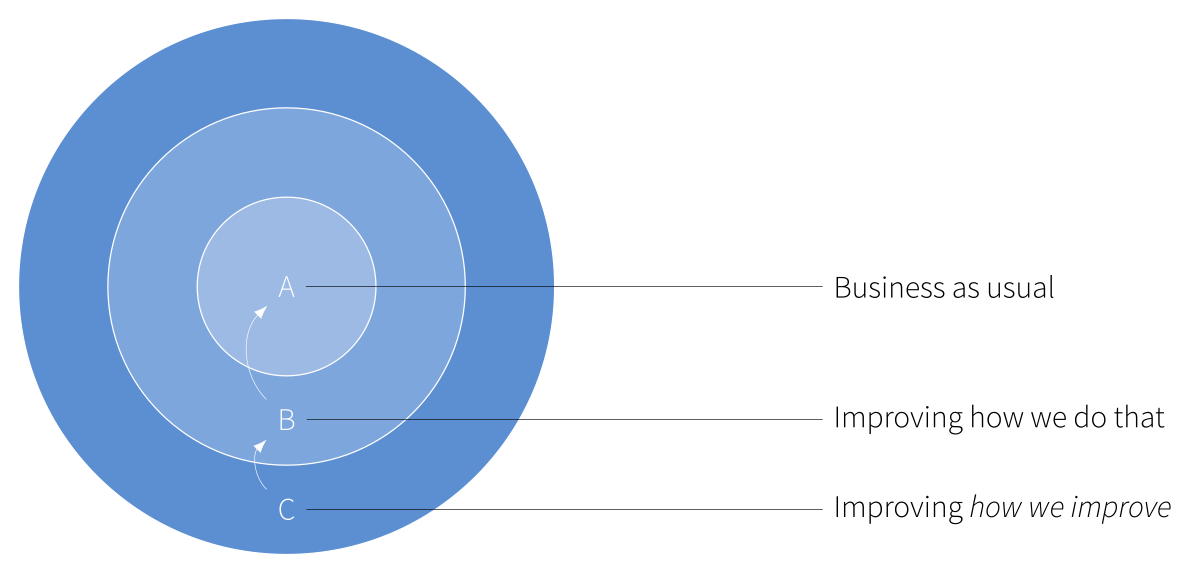

Doug Engelbart, one of the fathers of personal computing and one of my personal heroes, created a framework to illustrate this process. “The ABCs of Organizational Improvement” depicts three types of basic activities that should be ongoing in any healthy organization. We can also apply this model to the way we live our lives as individuals, and even to humanity as a whole.

Imagine three concentric circles, A, B, and C.

The innermost circle, A, is business as usual. These are the core activities and processes you can find in any organization: development, manufacturing, marketing, sales, programming, and so on. The core is all about executing today’s strategy. Before I had my first tricycle, this meant walking.

B represents the improvements we make by executing today’s strategy. For a business, this might include training, hiring, adopting new tools and processes, or bringing in external consultants. This is where we find tools and methods to make our lives easier and more efficient. My tricycle was an improvement over walking.

But C is where we go one step further, and improve on how we improve — like learning to ride a bike. How can we get better at inventing new processes in A and B? This is the most difficult thing to implement, but it brings the most value. This kind of meta-thinking is the shift from an incremental to an exponential improvement. And this is the key to advancing an organization. That same shift is the key to implementing technology in ways that benefit humanity.

Doing something is an A process. Optimizing A is a B process. Thinking about how to come up with new ideas for A and B is a C process.

Unfortunately, we seem to be trapped at B. We try to improve aspects of our lives and our world, but we seldom stop to ask if there are better ways to improve. Or how the journey to better possibilities would look.

Imagine I wanted to travel some distance. I might decide to walk, an A process. Then I might start to think about how I could get there faster. I might start exercising, run faster, buy running shoes, use a better route, or reduce the weight of my backpack. These are improvements to my initial activity, and each is a B process.

We need a C thought to ask if there are better transportation methods available — a bicycle, for example. The bike becomes the A process, and improvements to the bike are B processes, perhaps by getting a racing bike, for example. But we need to keep thinking about C.

And sometimes we do, but the trick is to continuously switch between all three thinking modes. We could ask if there are better ways to solve the problem. And if the true objective in traveling the distance is to have a conversation with someone, a phone call might be enough, and the journey itself becomes unnecessary. This is C thinking.

What we really lack in organizations, and as a society, is that we spend too little time with C thinking. We need to think about how we can get better at getting better.

And this is the key to the long-term viability of technology — for us, for society, for any organization: we need to get better at getting better.

Want more ideas like this in your inbox?

My letters are about long-lasting, sustainable change that fundamentally amplifies our human capabilities and raises our collective intelligence through generations. Would love to have you on board.