pencil and paper thinking

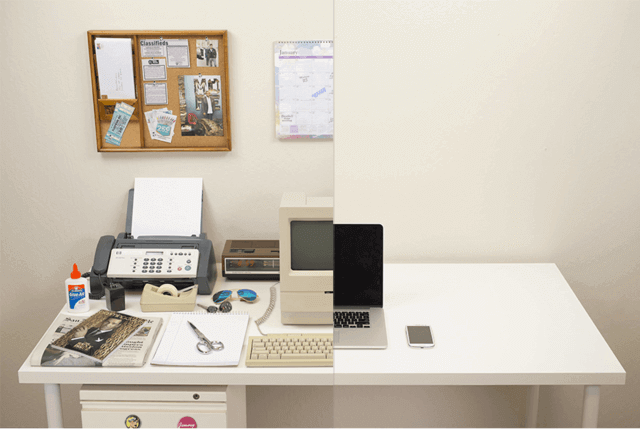

At some point you’ve probably seen the video by the Harvard Innovation Labs, demonstrating the steep progression from an ordinary office of the ’80s to today’s desktop.

The scene starts with vintage items, such as the original Macintosh, a corded phone, a fax machine, a Rolodex, the Encyclopedia or the Oxford Dictionary. Gradually, items are replaced by apps on the computer, until you are finally left with a clutter-free desktop holding only a modern laptop and a smartphone.

This video is a joy to watch. How much simpler everything is today! No need to depend on dozens of tools and devices all the time.

While watching this video I got stuck on one thing: all these devices and tools were replaced by their digital adaptations. But they were only replaced, not changed for the better — despite the thousand-fold improvement along every technological dimension.

The Rolodex was replaced by your contacts app, but its core is still the analog bundle of mostly-outdated information about your friends, colleagues, and peers.

A phone can still be dialed with a string of numbers like it was a hundred years ago, and we’re still forced to remember these numbers — or look them up when we need them.

When you open your favorite word processor you still see a blank page displaying an empty piece of paper. Why do we call these tools word processors when they are actually paper processors?

Most websites are mockups of papers as well. Text — line by line, and page by page. Maybe even an endless piece of paper, like your Twitter or Facebook timeline. Yes, we have hyperlinks, but are they really much more powerful than references?

Our keyboard and mouse are basically a typewriter on steroids. Sure, we rely on Copy and Paste, but a secretary from 50 years ago was pretty resourceful and ingenious.

Programming languages are written languages: they were designed to be written. We still code in text files, word by word, line by line. Programming languages limit the way we think about programming, so they limit the way we program, but also what we can imagine we can program.

Our apps are still as detached from each other as they were when they were physical machines on our desks, so it is almost impossible to transfer data between applications, which would enrich it in the process.

And modern user interfaces are almost identical to those in the initial Mac, and — you’ve guessed it — they were designed to resemble the medium of paper. Files are still represented as documents in paper folders that are placed on a desktop, moved into different folders, and deleted by dropping them into a trash bin.

Almost all of today’s representations are continuations from our past — more or less direct carryovers from the physical artifacts. Pencils and paper cost a few cents, but computers can cost thousands of dollars, even though computers are still limited to pencil-and-paper thinking, ultimately impeding our discovery of new ideas and approaches.

To quote Alan Kay:

It looks as though the actual revolution will take longer than our optimism suggested, largely because the commercial and educational interests in the old media and modes of thought have frozen personal computing pretty much at the “imitation of paper, recordings, film and TV” level.

In other words, our current approach limits our ability to invent more powerful ways of thinking about the world.

We are bound to the world we are born into. Our understanding is always limited by our knowledge, culture, and tools. With pencil-and-paper thinking we are limited to expressing our thoughts, ideas, and visions in words, drawings, and symbols. This was good enough for the past 1000 years, but is it enough for the next?

Every medium has natural limits to what we can do with it. A new medium initially liberates our thoughts and ideas, but only augments our abilities until we use it to full capacity. At that point, it limits and confines our expression of ideas. Most importantly, it prevents us from expanding into new ideas and creating new tools. By going beyond pencil-and-paper thinking we have a unique chance to expand our understanding of the world, to collaborate, and to address complex global crises.

We have to get away from pencil-and-paper thinking. To truly understand the world, we need tools far more powerful than pencil and paper.

The computer is in a unique position to become a dynamic medium that would allow us to understand, simulate, and modify complex systems, rather than just showing us static symbols on a screen.

We need powerful new modes of understanding that can draw on all the senses and skills humans possess, like touch, sight, hearing, spatial awareness, and physical movement.

We already know that computers can copy the old media and replace them with something that looks new. But what else can the new medium — the computer — really do?

Want more ideas like this in your inbox?

My letters are about long-lasting, sustainable change that fundamentally amplifies our human capabilities and raises our collective intelligence through generations. Would love to have you on board.